50 years ago on Saturday, January 20, 1974, the first General Dynamics YF-16 made its famously unscheduled first flight from Edwards AFB. On a high-speed taxi test, the YF-16 started oscillating in roll, scraping the stabilizer and left-hand dummy missile on the runway, and pilot Phil Oestricher decided he was safer in the air, landing safely after six minutes. It wasn’t an auspicious start to testing of an airplane that was widely regarded as something of a freak.

Artists’ concepts of the YF-16 hadn’t captured its unique appearance, so the arrival of the first air-freighted photos in the Flight International office, a few weeks earlier, had been an event.

A slender forward fuselage looked unable to accommodate any kind of radar. The frameless canopy was like nothing before it. The inlet cut way back. Small, almost F-104-like wings blended into the fuselage with root extensions reaching past the cockpit. Two AIM-9s – gadzooks, is that all? And a honking big engine nozzle. As the new trainee-grade sub-editor remarked, a “lightweight” fighter packing more thrust than an F-105. And from the famed home of agile fighters that brought you the F-111 and the B-58.

Much later, lead designer Harry Hillaker would point out that Fort Worth’s post-WW2 history was about doing things that were different from what had gone before them, so the team came to the requirement with a fresh mind. Hillaker had a few ex-Vought people on his team, too – the inlet resembles a cut-out F-8 inlet, check out the landing gear, and like the A-7 the fighter had a head-up display and central digital computer.

As for the big engine, Hillaker would quote Willy Messerschmitt: “Wrap the smallest aircraft possible around the largest engine you can find.”

The small radar and two AIM-9s came from the Fighter Mafia – the members behind the F-16 were Hillaker, John Boyd, and Pierre Sprey. Boyd brought the tactical experience, insisting on a return to the F-86’s all-round vision, while Sprey as a systems analyst mined combat data for what the aircraft did and did not need. Radar dish diameter, it turned out, affected the shape and size of everything behind it, to wit, the airplane. Air combat in Vietnam had been largely visual, MiG-17s had shot down F-105s and F-4s without radar; a ranging-only set would do. Next, the AIM-9 had been the only effective air-to-air missile in Vietnam.

Hillaker was no Luddite. Fly-by-wire was an extension of the stability-augmentation systems on the B-58 and the F-111 and allowed relaxed static stability. The wings did not sweep but the leading-edge flaps activated automatically to optimize lift and drag and make the small wing effective. On the YF-16, though, the structure was designed so that the inlet and leading edge extensions could be changed, and even the wing moved aft, if problems were encountered.

Problems were few, much less than the Northrop YF-17. Which was not really a competitor at the time of first flight, a situation that changed dramatically in April. Defense Secretary James Schlesinger announced that one of the two Lightweight Fighter prototypes would be the basis for 650 Air Combat Fighters for the USAF, with the clear intention of bagging the rapidly approaching European requirement for an F-104/F-5 replacement. The US decision was set for January 1975, ahead of the mid-1975 deadline for the European nations.

As we know, the F-16 won the USAF contract and scooped NATO against a divided opposition. There was some grumbling, not to mention jokes. (Two Russian generals are watching the victory parade on the Champs-Élysées, and one says “such a pity, Comrade, that we lost the war in the air”.) The Fighter Mafia purists decried the weight increase due to a multi-mode radar (half the weight of the F-4E’s APQ-120) and nuclear-weapon wiring. But within a few years, everyone loved the Viper.

“I’d rather be lucky than good” is a fighter-pilot maxim, but the F-16 was both. The airplane had a little growth potential – as a 2015 photo shows – although its basic dimensions have never changed. But there was some luck involved.

One early boost for the F-16 was that the AIM-9L Sidewinder missile turned out to be really good. The F-16 was also employed early and effectively by the Israel Defence Force, pre-empting a lot of arguments about its effectiveness. But the big factor was microelectronics, first manifested in the APG-66 radar. From that radar family to target designation pods, from jammers to displays, and in weapons carried (only the gun remains unchanged), the F-16’s tightly packed airframe has acquired capabilities that nobody dreamed of in the 1970s, when (paraphrasing Douglas Adams) we ape-descended life forms were so amazingly primitive that we still thought digital watches were a pretty neat idea. It’s why the airplane is still in production.

Less publicly, a series of Have Glass programs has reduced the airplane’s radar signature. Not to stealth levels, but enough to improve the effectiveness of jamming. It involves surface treatments and, errm, other methods such as treating radar bulkheads…

The F-16 has had a strong impact on international inter-service relations, the importance of which isn’t always appreciated. Before the F-16, most foreign air forces did not fly the same fighters as the USAF. Those that flew American flew hand-me-downs, F-5s, or F-104Gs, and by the time the F-104G entered service the USAF was retiring its earlier 104s. But today, the senior ranks of allied air forces are packed with F-16 pilots who have done exchange tours or flown on joint exercises with US F-16 units.

But the F-16 was not always that lucky. I met Harry Hillaker at Edwards AFB in 1983 during flight tests of the F-16-that-never-was, the F-16XL, a drastically modified airplane with a stretched body, no horizontal stabilizer and a double-delta wing based on NASA supersonic transport research. Originally intended to explore aerodynamics above Mach 1, the XL, even during its design phase, showed potential across the fighter envelope. While the wing did improve supersonic efficiency, two other attributes were important: between the new wing and stretched fuselage, the XL carried more than 80% more internal fuel than the F-16A, and the wing provided space for semi-conformal air-to-air missiles and bombs carried in tandem – each generating about half as much drag as the one in front of it. Range in many missions was doubled.

Unfortunately, the heavier airplane needed more power, and the USAF in 1983 was having enough trouble getting Pratt & Whitney to deal with the standard F100’s two minor problems (the first was that it tended to stop producing power and the second was that it was a bugger to get restarted). The F-15E Eagle was selected as the service’s next strike aircraft.

Ten years later, more powerful engines were in service. Hillaker was retired by then, but the Fort Worth team was looking at the fighter export scene, and the USAF was mulling where to go now that the 45-year adversary had folded. One option was to go with some dramatically improved versions of in-service airplanes, and in the last days of General Dynamics at Fort Worth (the GD unit was sold to Lockheed in March 1993. Lockheed, in turn, merged with Martin-Marietta in 1995), the XL concept was revived, with the United Arab Emirates as the prime target.

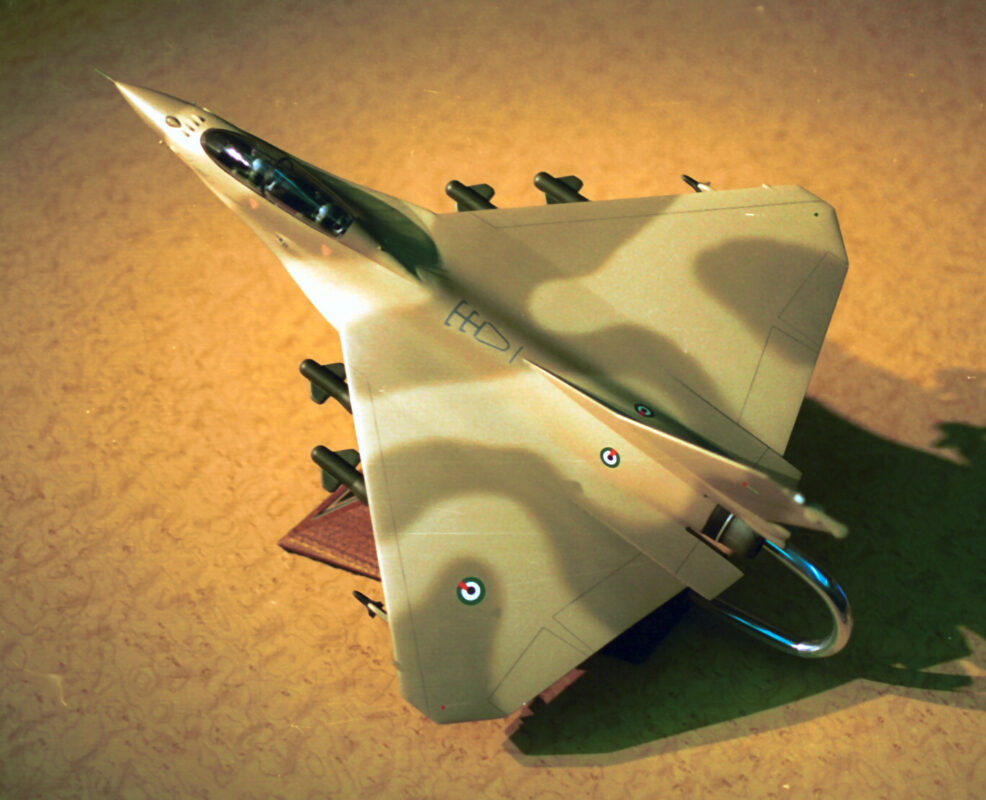

The new F-16U design was not far from the XL in basic numbers – fuselage stretch and fuel capacity – but the wing resembled that of the F-22. It would have an active electronically scanned array radar and internal optronics and be armed (for the UAE) with the Hakeem guided bomb family, of curious provenance. By 1995, Lockheed was closing on a deal, and a model was in the booth at the IDEX show in Abu Dhabi. It wasn’t officially shown in public, but when I went through on a morning photo-shoot it was out there on a table, so…

And that was the sanitized export model. Did you ever wonder how come the rakish diverterless inlet turned up on an F-16 in December 1996, when JSF demo contracts had only just been signed? It was part of a package of interesting features that would have gone on to the delta F-16 and would have been available for the US – and for the UK, who Lockheed was trying to get interested at a time when the Eurofighter was in trouble and the Germans were dithering over funding production.

The UAE, though, had one request: the USAF would have to buy a wing’s worth of the new airplane. But by then the Pentagon was getting enthused about a fully LO aircraft for the same price as an F-16. No deal. The UAE, instead, went with the more conventional and much less exciting Block 60.

Some years later, I was giving a workshop on fighter evolution to an audience that included a few Typhoon people. “It would have killed us”, one said. I agree. It would still be in production – and the Typhoon might not have been the only airplane it killed.

But one final, almost terrifying note. Go another 50 years back from the YF-16…

There’s a lot of concern in the security community every time Bill Sweetman says “errm”.